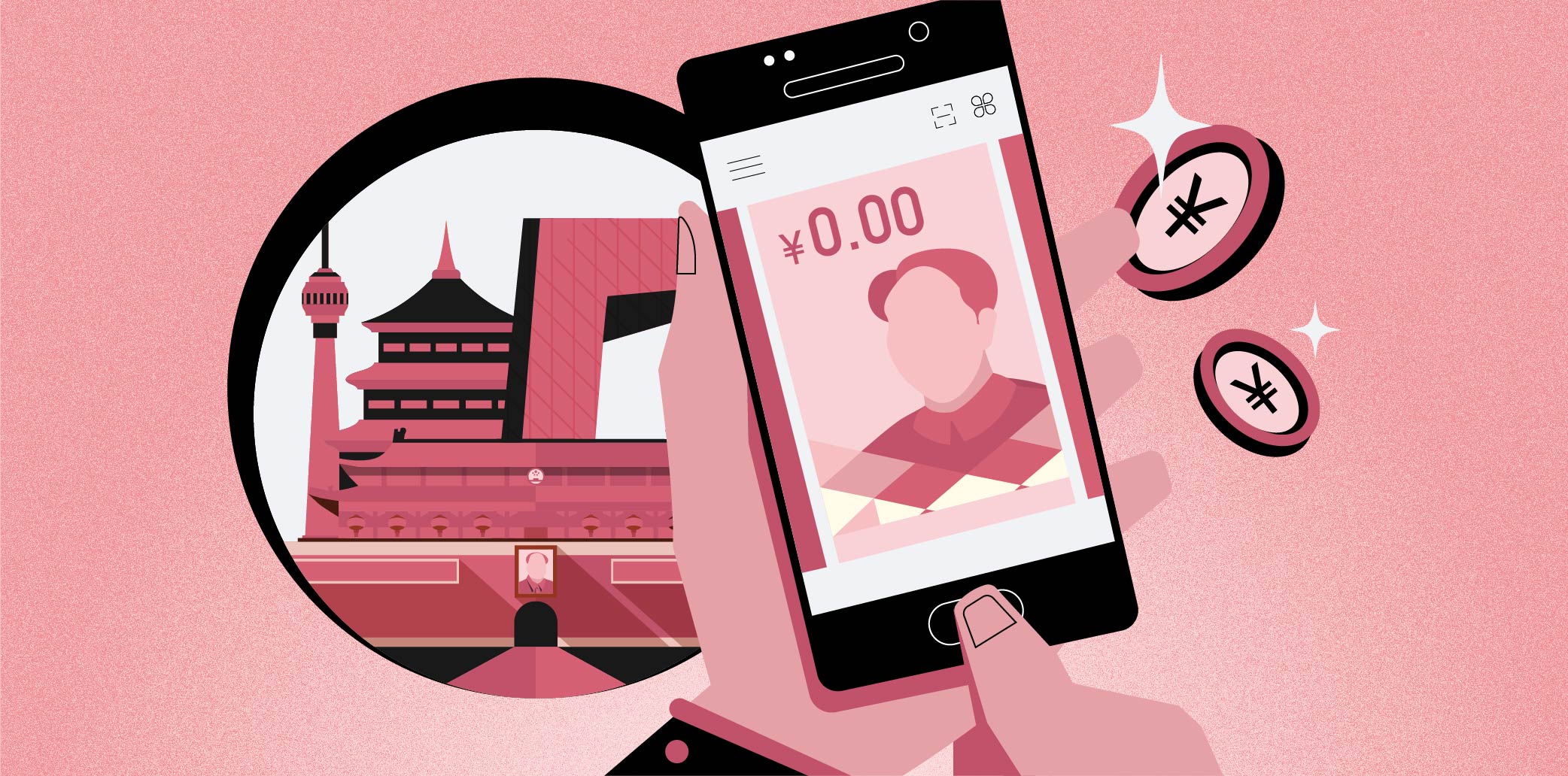

This year’s 618 online shopping festival was unusual. For the first time, the digital yuan, more formally called the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP) system, was part of JD.com’s signature annual sales event. Some 130,000 consumers spent RMB 21 million (USD 3.25 million) in e-yuan to buy all manner of JD’s proprietary products, the e-commerce operator said in late June.

Leading up to this rush of transactions was a series of public trials in Shenzhen, Shanghai, Beijing, and other cities that began last year. In all, RMB 279 million (USD 43.2 million) was given away to consumers for banks to gather data about their usage of the e-yuan, according to Mobile Pay Pass. This includes purchases made in physical stores.

Beyond this series of trials, where people received free cash to spend in designated stores, the digital yuan can be traded for cash at more than 3,000 ATMs in Beijing. It’s the world’s first sovereign digital currency, and I have been waiting to give it a go to see what all the hype is about.

How to set up a digital yuan wallet

The digital yuan is available for public use, but its standalone “Digital Yuan” app, which is operated by the People’s Bank of China, is not in any major app store. Downloads for its beta version are by invite only, so everyone else stores and uses the digital yuan through the apps of six designated state-owned banks.

The process isn’t intuitive, so I headed to a bank to get some help. Within two hours, I had two e-CNY wallets from the Bank of China (BoC) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC).

Read this:China’s digital yuan is now available to individuals and corporates in Shanghai

By looking at the UI, it’s clear that much is being done to lay the groundwork for linking the digital yuan to existing payments and banking services. It is connected to around 25 other services (depending on the bank) through “sub-wallets.”

In particular, the Digital Yuan app links up with banks’ wallets to make them all accessible on the same screen. There are also two private online banks that are part of the DCEP’s distribution and processing network—Tencent’s WeBank and Alipay’s MYbank—although neither has been fully integrated.

Aside from small-scale consumer spending, the digital yuan is being used by some Chinese Communist Party members to pay their party dues. This aligns with the general development of the DCEP being used in contexts beyond consumer spending, like salary payouts, utility payments, or public functions like social security and taxes.

The DCEP is not widely accepted yet

In Chaoyang district, where the Beijing office ofKrASIA is located, at least 847 distinct businesses accept the digital yuan. It’s the highest number among the capital’s districts, according to local news outlet Beijing Business Today. This includes 60% of eateries along Xiaoyun food street and 48% of the merchants in Sanyuanli market as of mid-June, according to a Beijing Commerce report.

The central bank’s objective seems to be to roll out the DCEP in popular tourist areas and business districts; this makes sense as it provides a high volume of transactions to observe behavior and gather relevant data like transfer sizes and frequency.

However, that goal is at odds with what’s actually happening.

At the end of June, I paid a visit to Chaoyang, looking for signs posted by vendors that say they accept the digital yuan as a payment method. After visiting nearly 80% of the food street’s restaurants and eateries in Xiaoyun to ask whether they take digital yuan, the response was almost always a baffled look from the staff. I wasn’t able to locate the food street’s management to verify the claims in Beijing Commerce.

The merchants at Sanyuanli fared better on the surface, with 60% of the stores posting signs indicating that digital yuan payments are welcome. But attempts to use the DCEP were met with rejections, with some clerks saying they were not trained to use the app and process e-CNY, or that instructions left by management were unclear.

I did eventually locate one shopkeeper who was able to process DCEP payments. The daughter of a fruit stand’s owner who looked like she was in her 20s happened to be there and was able to help. I’m proud to say my first purchase with digital yuan was a giant watermelon. It cost 82 renminbi.

The transfer was smooth and involved scanning each other’s QR codes, just like when using Alipay or WeChat Pay. Other options are entering the payee’s phone number or using the “Touch” NFC function, making it possible to move funds even if both parties are offline.

This test run over one weekend demonstrated that people, in general, weren’t ready to switch over to the DCEP; channels like Alipay and WeChat Pay have been around for years and, for many, are convenient enough options. Furthermore, Alipay and WeChat Pay are entrenched in the daily spending habits of many Chinese consumers. They function as more than payment methods and incorporate other features to give people a reason to use them every day. The DCEP, on the other hand, only has one function—to transfer cash balances from one wallet to another.

But what about popular online services like e-commerce, rides, meal delivery, and online travel agencies? Would it be easier to spend the digital yuan on these platforms?

As it turns out, there are plenty of limitations. The digital currency can only be used for specific services, and there are geographical restrictions.

For example, on Meituan, China’s biggest food delivery platform, the digital yuan can only be spent on groceries and shared bicycles. While it can also be used to settle dine-in restaurant bills, this is only valid at some locations in Shanghai. On JD.com, the e-yuan is accepted only for orders of JD’s proprietary products, which are mostly daily necessities like napkins and face masks.

A tough sell

Experts expect the digital yuan to be officially rolled out nationwide after the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, per Shanghai Securities News. However, before then, the government believes foreigners, both those living in China and visiting for the Olympics, can provide a trove of test data about the DCEP, especially from those who cannot use Alipay and WeChat Pay as they do not have local bank accounts.

Choosing Chaoyang District for the digital RMB pilot was a strategic decision because it’s in line with the characteristics of the locale. “Chaoyang District has frequent business activities and a high degree of internationalization. The district includes a large number of consumption scenarios, and the age structure and income structure of residents can meet the pilot’s needs,” according to Wang Peng, an assistant professor at Renmin University of China, in an interview with Beijing Commerce.

But for Chinese citizens in top-tier cities, there is little motivation to switch over at the moment. After the central bank’s lottery, which awarded free digital yuan for the trials, few have sought to exchange their cash for digital yuan. The shop owners in Sanyuanli were surprised that I had traded cash for e-CNY on my own. “We’ve only had two people pay with digital yuan, and only because they won the red packet lotteries,” one said.

Banks are handing out gifts to anyone who registers for a DCEP wallet. One employee at a bank branch in Beijing told China Securities Journal that sign-ups are now part of daily assessments.

Behind these efforts is the Chinese government’s intention to internationalize the yuan and elevate its global status. Starting with stable domestic use, the goal is to facilitate cross-border transfers with countries that are part of the Belt and Road Initiative first, according to Sina News.

Digital yuan > Alipay & WeChat Pay?

For merchants, the advantages of utilizing the digital yuan are clear—no registration fees, commission fees, or other charges.

However, consumers have other details to consider. After using the digital yuan for a week, will I ditch Alipay and WeChat Pay? The answer, at the moment, is no. Even though the user experience is smooth, far too many functions are still under development, and shops don’t seem rushed to add it to their payment methods.

Though there is one group that will significantly benefit from the digital yuan—China’s unbanked population, who made up more than 11% of the total population in August 2020. The e-CNY could help fold them into the formal financial system and close part of the digital gap, as it requires no bank account to register for a digital yuan wallet.

What’s more, the central bank has highlighted the ability to track payments as a security feature of the DCEP without infringing on personal privacy as “institutions cannot link users’ phone number to the transactions,” according to Mu Changchun, director of the Digital Currency Research Institute of the People’s Bank of China, when he spoke at this year’s China Development Forum.

Furthermore, the “sub-wallets” function will hide users’ digital footprint from third-party online service providers and payment platforms, making sure they cannot access users’ personal information or transaction records, said Xinhua News.

Even though representatives of the central bank have said DCEP is meant to work alongside existing payment channels, the rhetoric hardly matches the practice. I asked an ICBC bank clerk whether everyone in the country is expected to eventually have a digital yuan wallet. His response was clear: “Yes, for sure. It will replace Alipay and WeChat Pay in the future.”

Watch this:5 things you need to know about China’s digital yuan